The valley of the Jordan is called by the Arabs the ghor. In the Hebrew Bible the same region is called ‘arabah, though all the Scripture allusions to it refer to the southern part, the kikkar, or its immediate neighbourhood. ‘Arabah means “dry plain or valley,” a good description of this deep, hot, close, arid vale, in the southern end of which rain rarely falls, though the greater part of it was formerly a scene of the utmost fertility owing to copious irrigation from springs at the foot of the mountains on either side, and from aqueducts supplying water from the upper reaches of the river. When Lot looked upon it from a high hill between Bethel and Hai, he “beheld all the round plain [kikkar] of Jordan, that it was irrigated [literally, ‘drinking’] all of it, before Jehovah destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah, like a splendid garden [literally, ‘a garden of Jehovah’], like the land of Egypt, in thy going to Zoar,” that is, up to the very foot of the mountains of Moab. (Gen 13:10)

Down the centre of the valley runs a trench, a valley within the valley, about thirty feet to fifty feet below the rest, with a breadth varying from a quarter of a mile to a mile, which is a true wilderness, absolutely waste and dry during the hot season, as are the white marl cliffs which bound it on both sides; and there is every appearance of its always having been the same. This explains Josephus’ statement—so much at variance with what he tells us of the ‘arabah at large—that the Jordan flows “through a desert.” This deep, barren trench is called by the Arabs the zor, or “throat,” that, is, “the throat of the river,” to distinguish it from the rest of the valley, the ghor, which rises on each side, in most parts some thirty feet above it.

Down the centre of this lower part of the valley the Jordan flows, very swiftly, with endless snake-like windings, quite a small, insignificant, turbid, coffee-coloured stream, for some nine months of the year. Well might Naaman, a proud, unconverted man, when told by the prophet to go and wash in Jordan, cry of those wide, pure, crystal streams that still irrigate the plains of his Syrian home, “Are not Abanah and Pharpar, the rivers of Damascus, better than all the waters of Israel?” But Jordan is considerably wider when, about April, the snows of Anti-Lebanon begin to melt, and pour a flood down the river for some two or three months, for to this day “Jordan overflows all its banks all the time of harvest.” But even then it is only about seventy yards wide. (2 Kings 5:12; Joshua 3:15; Joshua 4:18; 1 Chronicles 12:15)

Partly in consequence of this overflow, and partly owing to the great heat—it is sometimes 100° Fahrenheit in the shade here as early as April—on each side of the river there rises a rich sub-tropical jungle, tangled thickets of trees, shrubs, and creepers, conspicuous amongst them the elegant Jordan reed (Arundo donax), from twelve to fifteen feet high, gracefully waving its immense panicle of plume-like white blossom, “so slender and yielding that it will lie perfectly flat under a gust of wind, and immediately resume its upright position”—”the reed shaken by the wind,” which our Lord implies was a striking feature of natural beauty on the banks of the Jordan, flowing through its “wilderness,” where John was baptising. Itself a lonely jungle, and situated in the midst of a desert, it is naturally the lair of wild beasts, and so it must have been in ancient times.

This annually irrigated rich wild growth, one of the most luxuriantly verdant sights to be met with in Western Palestine, the beauty of which is greatly enhanced by contrast with the wilderness tract that surrounds it, was well called in Bible times “the pride of Jordan.” The Hebrew word “pride” here, ga-on, occurs some forty-six times in the Old Testament, and is translated in every instance in our Authorised Version with the signification of “pride.” Thus our translators have rendered it in Zechariah:

“The pride [ga-on] of Jordan is spoiled.” (Zech 11:3)

Speaking of the Chaldean invasion of Edom, Jeremiah says:

“Behold he shall come like a lion from the pride of Jordan.” (Jer 49:19)

Lions, it is true, no longer infest the jungle on the banks of Jordan, but to this day bears, leopards, hyenas, wolves, jackals, and wild boars find comparatively undisturbed lairs here, and they could hardly secure a warmer or more suitable dwelling-place. Some have supposed, owing to the mistranslation of our Authorised Version, “the swelling of Jordan,” that the allusion is to the lion’s being driven out at harvest time, when the river overflows its banks. But this is a misapprehension, for at such time, even in the highest floods, miles of this dense cover are not under water, and it is not a fact that any wild beasts are necessarily driven out into the country at that season.

It will be seen the explanation I give is in complete accordance with the obvious meaning of the same bold figure employed by Jeremiah in another well-known passage:

“For thou hast run with the footmen,

And they have wearied thee.

Then how wilt thou fret thyself with horses?

And in a land of peace where thou has trusted

[They have wearied thee].

Then how wilt thou do in the pride of Jordan?” (Jer 12:5)

Here “the land of peace,” that is, “the peaceful land,” the safe place of human habitation is finely contrasted with “the pride [ga-on] of Jordan,” the tangled, pathless jungle along its banks, the haunt of wild beasts!

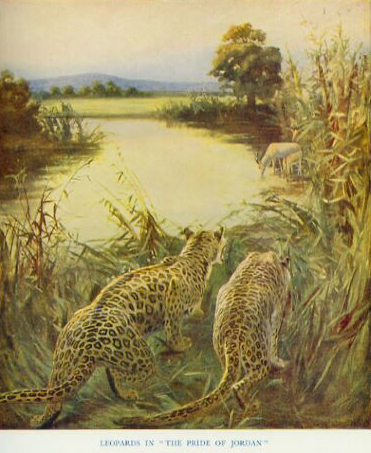

Our picture shows “the pride of Jordan” seen at eventide on a short reach of the river. In the foreground are two leopards stalking a roebuck and a gazelle that have come down to drink at a watering place. The leopard, or panther, the namar or nemar of the Hebrew Bible, the nimr of the Arabs, is a very powerful beast of prey, “but little smaller than the Asiatic lioness, and occupying the same place in the economy of nature that the Bengal tiger does in India.” The names of places, such as Beth-Nimrah, “house of the leopard,” near the Jordan, probably at the stream now called by the Arabs Nahr – Nimreem, “river of the leopards,” and the “mountains of the leopards,” show that this fierce feline was formerly common in the Holy Land. “Mountains of the Leopards” is very suggestive of this animal’s constant habit of spending the day sunning itself on the crags of lonely, inaccessible cliffs on the summits of mountains; unlike the lion, which keeps always on the low, hot plains. At night the leopard stealthily descends, and hunts in the valleys and plains for its prey, travelling in this way sometimes as far as thirty miles in a night.

It can be recognised at a glance by its yellow spots ringed with black, which gave it its Hebrew name, namar, “spotted”; for, as the prophet cries:

“Does an Ethiopian change his skin, or a leopard his spots?” (Jer 13:23)

It is taken as a type of fierceness in that picture of the millennium, where we read, “The leopard shall lie down with the kid.” Nor could any animal be fitter for the purpose of portraying savage strength than the leopard; for every other wild beast seems to fear it, and the night when a leopard is about is ominously still, for no other “beast of the open land [sadeh]” moves or cries! Fortunately it only remains in one spot three nights, and then seeks other hunting-grounds; and darkness in the desert is again noisy, to the immense relief of shepherd and sheep, who know only too well why the wild boar has ceased to tramp, the hyena to scream, the wolf to bay, and the jackal to yell, preferring to fast rather than run the risk of falling a prey to the dreaded nimr.

The cunning and perseverance of this animal cause it to be feared as much as its strength and fierceness. Crouched like a huge cat, it will lie motionless for hours, waiting at the entering in of a village or at some watering place, until its prey comes within striking distance, when, with one huge bound from an almost incredible distance, in a flash—for the leap of a leopard is swifter that that of any other mammal—it is on the back of its victim, and is strangling it by burying its fangs in its throat.

In allusion to this dangerous habit of waiting for its quarry, the prophet cries:

“A leopard shall watch over their cities.” (Jer 5:6)

While the Most High Himself declares of His sinful people Israel, in words of awful significance:

“Like a leopard by the way I look for [them].” (Hosea 13:7)

Its swiftness also forms a Scriptural figure, for in Habakkuk 1:8 it is said of the efficient mounts of the Chaldean cavalry, “Their horses are swifter than leopards.” For this reason a winged leopard is chosen, in the vision of successive Gentile dominions, to image Alexander the Great and the Greek empire, because, swift as a panther’s spring upon its prey, the Grecian commander conquered the world in thirteen years, a feat of arms unparalleled in history. (Dan 7:6)