Excerpt from Everyday Life in the Holy Land by James Neil

Chapter 4

There are no pastures in Palestine as we understand them. Throughout the East grass is never sown or cultivated, and is never made into hay. Where we use hay, they feed with teben, “crushed straw,” and give barley to horses instead of oats. It was just the same in Bible times, for we read that Solomon’s officers provided his stables with “barley and crushed straw [teben] for the horses.” The grazing grounds of the Orient are either the common, unenclosed arable lands round the village, the sadeh, at such time as they lie fallow, or the deserts which occur in and around these lands. The rich, spontaneous growth of the sadehs affords good feed, and for a portion of the year the flocks can be kept on this supply. For two months in the spring they can be turned out upon those fields, which, being kept for summer crops, are not sown till late in April; and from July to October they can be transferred to the stubble lands from which the winter crop has been reaped. But these are not, strictly speaking, the proper pastures of Bible lands.

Such pastures invariably consist of lonely, unfenced, uncultivated desert hills and plains where no dwelling is to be seen, save the low black tents of the bedaween. They are no mere sand wastes, being covered in spring with a glorious wild growth–a sight of much brightness and beauty during February, March, and April–with here and there a shrub or stunted tree and a good deal of woody, persistent growth for the rest of the year, during which they present a very barren appearance.

The usual word in Hebrew for “desert” or “wilderness” is midbar, from dabar, “he drove,” because they are the places where the flocks and herds are “driven” for pasturage. This answers to the prairie-like “sheep runs” of our Australian bush. It is there called “a run,” because there are no wild beasts or organized bands of sheep stealers, but “a drive” in Syrian deserts, because, owing to wild beasts and wilder men, the bedaween and brigands, the shepherd has to “drive” them, be constantly with them for protection, and drive them home again to the shelter of their fold. Hence we read in the Old Testament of the “pastures of the desert,” that is, “desert pastures.” (Ps. 115:12; Isa. 32:14; Joel 1:18-20)

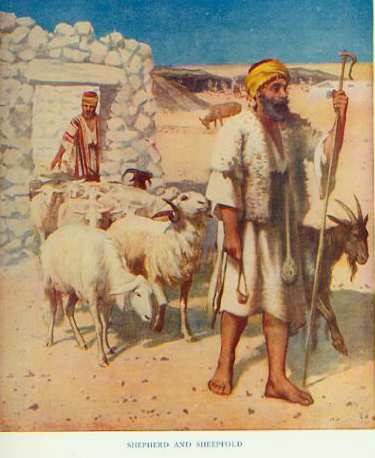

Our picture shows a part of such a “pasture of the desert,” seen in the hot season, with a Palestine shepherd in the foreground. Observe his shaivet or shevet, the oak club, rendered “rod” in our Versions. The dangers of wilderness pastures have always called for this weapon of offence. It is borne by the Eastern shepherd as well as a staff or crook.

In allusion to the purpose of protection for which this formidable weapon is employed, the prophet Micah, calling upon Jehovah to come to the deliverance of His people Israel, cries,

“Shepherd Thy people with Thy club,

The flock of Thine inheritance”. (Mic. 7:14)

There is another very interesting allusion to the use of this club, where we read,

“I will bring you out from the peoples,

And assemble you from the lands

In which ye have been scattered…

And I will bring you into the wilderness of the peoples, …

And I will cause you to pass under the club [shaivet]: …

And clear out from you the rebels,

And those transgressing against Me:

From the land of their sojournings I will bring them out,

And they shall not come into the land of Israel.” (Ezek. 10:34-38)

This metaphor of “passing under the club” receives light from Leviticus 27:32: “All the tithe of the herd and of the flock–all that passes by under the club–the tenth is holy to Jehovah.” It was the way of taking the tithe of sheep and cattle. As Jewish writers have recorded, it was usual, when the tenth was being taken, to bring all the animals together and place them in a pen, or in the sheepfold, such a fold as is shown in our picture. They were then allowed of themselves to pass out one by one through the narrow entrance, where the shepherd stood with his club, the rounded head of which was dipped in a bowl of coloring matter. As the beasts came out–thus themselves arranging the tithe with perfect impartiality–he let the rounded head of the club fall on every tenth, marking it with a spot of color; and those thus branded were taken for the purpose of slaughter as sacrifices. Here we have in Ezekiel the gathering together of Israel out of the countries where they are now scattered, and at the same time the purging out from among them of the rebels, both strikingly set forth by this illustration of gathering together a flock to take out of it the tithe. It should be borne in mind that sheep and goats in the East are kept almost entirely for their milk and wool, and are never killed to be eaten except in the form of sacrifices.

Thus “passing under the club” implies the two purposes for which Israel are yet to be restored–first, a final and purifying judgment; and secondly, their conversion as a nation, and their complete and glorious restoration to Emmanuel’s land. For the passage closes with the promise–

“For in My holy mountain,

In the mountain of the height of Israel, saith Jehovah,

There shall all the house of Israel serve Me,

All of it in the land–there I accept them…

With sweet fragrance I will accept you, …

And I will be sanctified in you

Before the eyes of the nations. (Ezek. 10:40, 41)

The shepherd is seen holding in his hand a sling, such as he makes himself. These slings serve very much the purpose of sheep dogs with us, in rounding up the sheep and keeping them together. The shepherds are very skilful in the use of these weapons, and when they see one of the flock straying too far they cast a stone, often to an immense distance, but with so sure an aim as not to hit the sheep, but to let the missile strike the ground near enough to thoroughly frighten the animal and so bring it back. As these slings are in constant use, shepherds of all men are most expert slingers. When, therefore, David the shepherd boy, who was evidently proficient above most in the use of this truly formidable weapon, advanced so boldly upon Goliath he was justified in the hope of victory; for at close quarters such a stone received on the forehead would stun the strongest man. As to accuracy of aim, we read, that of Benjamin, “there were seven hundred chosen men, left-handed, every one could sling stones at a hair’s breadth and not miss,” which, though, no doubt, the rhetorical trope of hyperbole, or exaggeration, as common in Holy Scripture as it is in the speech of the East today, denotes a degree of marksmanship, at a short range, equal to that of an expert rifleman. (Jud. 20:16)

Slingers formed a regular corps in Eastern armies, especially in the army of Israel.

We read, in the attack on Moab, that at the city of Kir-hareseth “the slingers went about it, and smote it.” King Uzziah prepared for his “army of fighting men” amongst shields, spears, helmets, bows, etc., “stones for slinging,” which are mentioned as distinct from the “great stones” he had for catapults. These sling stones are always “smooth stones” taken from the rough torrent beds, where they have been ground smooth, and kept in the shepherd’s “scrip,” or “small leather bag.” A regiment of slingers could always be got together from these stalwart shepherds, who, from the nature of their calling, are some of the strongest, bravest, and most self-reliant of men.

The short, reversible sheepskin jacket the shepherd is wearing, called in Arabic furweh, is peculiar to the fellahheen. This poor, rude garment–sometimes made from the skin of a goat–though, like all other clothing of men and women in the East, picturesque in its way, is one of their roughest features of dress, and a mark of poor working men. It seems to be for this reason alluded to by the Apostle Paul in his letter to the Hebrews–the Palestinian Jews–when, telling of the trials of believers under the Old Covenant, men “of whom the world was not worthy,” he says, of the poverty and distress to which persecution brought them, “they went about in sheepskins, in goatskins, being destitute, afflicted, evil-entreated.” (Heb. 11:37)

The sheepfold is here shown, a simple structure, the enclosure wall of which is a jedar, a wall peculiar to the Palestine mountains, formed of rough, shapeless stones, the waste of the quarries, laid skillfully together, the large pieces outside and the small within. A jedar is about three feet wide at the base, tapering up to about one foot wide at the top, and from four to eight feet high. No mortar of any kind is used, the jagged, irregular stones being laid so as to fit closely and firmly together. No foundation is dug, the jedar resting on the smoothed surface of the ground. This is undoubtedly the gadair or geder of the Hebrew Bible, for the hard “g” of Hebrew always becomes the soft “j” in similar Arabic words. The feminine form gedairah is generally used for “folds” for sheep, just as the Arabic form jedarah is today; showing that in ancient times, as now, they consisted largely of these loose, unmortared walls. (Numb. 32:16; 1 Sam. 24:3)

They have no door, the one entrance being a narrow opening in the wall. Here, when guarding the sheep at night, or admitting or giving them egress by day, the shepherd takes his place, and, quite blocking up the entrance, is himself virtually the door; and this, surely, is the allusion of our Lord when, speaking of the fold of His sheep, His flock the Church, He says, “Amen, amen, I say to you–I am the door of the sheep …I am the door; through Me if anyone come in he shall be saved, and he shall come in and go out, and find pasture.”

Aqueducts are, and always must have been, very common and familiar objects in the Holy Land, where the scarcity of springs and perennial streams, the entire absence of rain for some seven continuous months of cloudless heat all day, and the universal and extensive practice of horticulture render them so necessary. Ruined remains of such aqueducts are everywhere to be met with throughout the country, some of a most costly and elaborate kind. It is therefore almost certain, first, that the inspired writers must have alluded to these precious water channels; and secondly, that in the primitive, rich, precise Hebrew of the Old Testament there must be a special technical term for them. Now there is a word which our translators have clearly misunderstood, apheek, from the root aphak, “restrained,” and which occurs in the names of places, as Aphaik, near Bethhoron, the feminine form Aphaikah, near Hebron, spelt in our versions Aphek and Aphekah respectively. Though the word only occurs nineteen times, it is rendered by no less than seven different terms in our Authorized Version, and the one used most frequently (ten times), “river,” cannot possibly be its true sense. But the meaning “aqueduct” gives the true rendering in every case, the pipe, or channel, that contains or forces a stream of water to flow in any required direction; though apheek appears in some cases to be applied by way of metaphor to the natural subterranean channels which supply springs, and the narrow, rocky, aqueduct-like beds of some mountain streams.

Thus in our Authorized Version it is said of behemoth–the “hippopotamus”–

“His bones are strong pieces of brass,” (Job 40:18)

which has no appropriateness of any kind, whilst there is no conceivable reason for rendering apheek “strong pieces.” But the boldness and beauty of the hyperbolic figure appears at once if we translate it properly, “His bones are aqueducts of copper,” hardened copper, the strongest metal of the ancients, answering to our steel.

This explanation gives new and especially forceful meaning to the opening words of Psalm 42. These are literally:

“Like the hind pants [or ‘brays’] over the aqueducts [apheekaiymayim],

So pants my soul after Thee, O God.”

In both our Versions it is rendered “panteth after the water brooks.” But a deer would not “pant” or “bray” for water if it were standing over an open stream. The whole force of the simile is lost in our English Bible. This psalm bears marks of being written at the season when David was compelled to fly from Jerusalem by Absalom’s rebellion. Away on the mountains of Gilead, yet in sight of the sacred region of Zion, which he could look down upon but could not reach, he is lamenting the inaccessibility of those spiritual privileges, precious, as “living waters,” which he had enjoyed at the Tabernacle at Gibeon, only five miles away from his home in the Holy City, as well as at that Tabernacle he had made for the Ark in Jerusalem itself, at which he had arranged continual services. “He thirsts after God, and longs to taste again the joy of His house, like the parched and weary hind, who comes to a covered channel, conveying the living water of some far-off spring across the intervening desert. She scents the precious current in its bed of adamantine cement, even hears its ripping flow close beneath her feet, or perchance sees the living water through one of the narrow air-holes; and, as she realizes the inaccessibility of the draught, she lifts up her head in her anguish and ‘brays over the aqueducts.’” This scene is shown in the center of the picture.