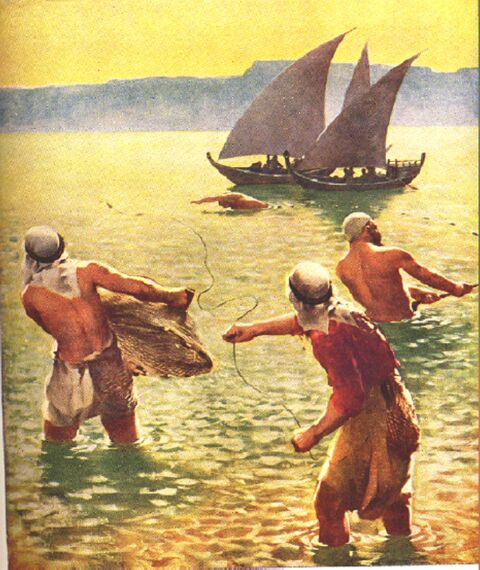

On this account the fishermen here work stark naked, with sometimes a little skull cap on their heads; and they are the only workmen in Palestine who do, for nakedness is thought shameful. This strange custom is incidentally noticed in the Gospel by John the fisherman, when he tells that Peter, before leaping out of the boat to swim ashore to his Master, “girt his fisher’s garment upon him, for he was naked.” It would seem to have been one of our Lord’s fisher followers, who, at His arrest in the garden of Gethsemane, had “a linen cloth cast about his naked body,” and when, in trying to take him, they seized the linen cloth, “he fled from them naked.” On the Egyptian monuments men fishing with nets are depicted naked. (John 21:7; Mark 14:51, 52)

Fishing in the lake is chiefly carried on from the shore. At Ain Tabigah on the north shore, towards the west of it, is a spring of warm, clear water, and here the vast shoals gather from time to time. The only other spot where this occurs is on the eastern side of the north shore, where the Jordan enters the lake, and the fish are attracted by its fresh, cool waters. I made this discovery of these only two regular places of fishing during a journey in this region in 1872, and at once perceived that these must be the two Bethsaidas, or, as the words means, “places of fishing,” plainly alluded to in the Gospels, but which the commentators could not locate. The western Bethsaida was at Ain Tabigah. This was the place from which Philip came, and “the city of Andrew and Peter” (John 1:44); of which Christ said, “Woe unto thee, Chorazin! Woe unto thee, Bethsaida!” (Matt 11:21; Luke 10:13); and of which we read, when Christ was at the northeast of the Lake of Gennesareth, “He constrained His disciples to get into the boat and to go to the other side over against Bethsaida.” (Mark 6:45). The splendid ruins of Chorazin are about two miles and a half to the north of it. The eastern Bethsaida stood somewhat back from the shore near to where the Jordan enters the lake. Here Christ gave sight tot he blind man who saw at first “men as trees walking” (Mark 8:22-26); and here, in “a desert place belonging to the city called Bethsaida,” the Lord fed the five thousand. (Luke 9:10-17) Later on Philip the Tetrarch rebuilt and adorned this Bethsaida, and called it Julias after the daughter of the Roman Emperor.

There are three ordinary methods of fishing from the shore when the shoals come to Ain Tabigah, or to where the Jordan enters the lake. One of these is by a line with baited hooks – fly-fishing is unknown in the East. Isaiah speaks of “all that cast a hook into a stream.” When miraculously providing the money to pay the half-shekel, or two drachmas (one shilling and threepence), the “redemption money,” for Himself and Peter, one of the most astounding of all His miracles, the Lord said, “Go thou to the sea, and cast a hook, and take up the fish that first comes up; and when thou hast opened its mouth, thou shalt find a stater [a coin equal to two half-shekels, two shillings and sixpence]: that take, and give unto them for Me and thee.” (Ex. 30:11-16; Matt 17:27)

Another way of fishing is by the cast net, the amphibleestron of the New Testament. This net is in the form of a bag, coming to a point at the bottom, to which a long rope is attached. It has a mouth about three feet in diameter, with weights around it which keep it open when thrown, and close it when it sinks through the water. Sometimes this is used from a boat. When used from the shore, the fisherman wades or swims in, and throws it with great dexterity to a considerable distance, and then draws it in by the rope. This was the net that Simon and Andrew were employing when Jesus called them to follow Him and become “fishers of men.” (Matt 4:18; Mark 1:16)

There was evidently a very large form of this cast net, called in the New Testament diktuon, too heavy to be thrown to a distance, which was used from the side of a boat when the fishermen found themselves in the midst of a shoal. It is mentioned as employed under these very circumstances when our Lord bid Peter and his fellow fishermen “cast the net [diktuon] at the right side of the boat,” and they obtained an immense haul, 153 great fishes, and (which seems a part of the miracle) the diktuon remained unbroken. (John 21:6-11)

A third common mode of fishing, sometimes from the shore, but more often from the boats, is with a long seine net, the drag or draw net, like our own, with floats at the top and weights below. This is once mentioned, the sagene (from which Greek word our name “seine” comes), as the net drawing great numbers of fish of all kinds, good and bad, to which the Kingdom of Heaven, in the sense of the professing Church, is compared. (Matt 13:47)

Fishing by the boats is mainly done at night. The seine net is put out on the lake, and two or three of the boats, with flares of oiled rag burning in an iron cage in the bow, the fishermen making a loud noise by beating old metal pans together, drive the fish towards the net. This is the usual method of fishing away from the shore, and it can only be done at night. Hence the great trial to their faith, in the case of those experienced Galilean fishers, who, “having labored all night and taken nothing,” were bidden by the Master, now that it was day, to “put back to the deep,” and let down their “great cast nets [diktuon] for a draught.” But they obeyed, and found themselves at once in the midst of a vast shoal, so that the overfull diktuon was broken in pulling it in; and, notwithstanding this, the haul filled tow boats, so as nearly to sink them. (Luke 5:4-6)

The boats are usually manned by four to six men, and boast a single sail. They are pointed at the stern as well as at the bow, and have a covered, cabin-like, small deck shelter at the stern. This extends for a few feet, and is open at the side facing the bow, where the fishermen, when off their watch, can get some protection from the weather, and rest their wearied heads, or, rather, the nape of their necks, on the tiny, hard, stuffed leather roll, about a foot long and four to five inches in diameter, which they employ as a pillow.

It was here, and in this way, that the Lord rested during a great storm; for, sheltered to some extent from the violence of winds and waves, “He Himself was upon the stern, upon the pillow sleeping.” (Mark 4:38)

Sir Charles Wilson thus describes one of these sudden storms. “The morning,” he writes, “was delightful’ a gentle, easterly breeze, and not a cloud in the sky to give warning of what was coming. Suddenly, about midday, there was a sound of distant thunder, and a small cloud, ‘no bigger that a man’s hand,’ was seen rising over the heights of Lubeik, to the west. In a few moments the cloud had spread, and heavy black masses came rolling down the hills towards the lake, completely obscuring Tiberias and Hattin. At this moment the breeze died away; there were a few moments of perfect calm, during which the sun shone out with intense power, and the surface of the lake was smooth and even as a mirror. Tiberias and Mejdel stood out in sharp relief from the gloom behind, but they were soon lost sight of as the thunder gust swept past them and, rapidly advancing across the lake, lifted the placid waters into a bright sheet of foam. In another moment it reached the ruins of Gamala, on the eastern hills, driving my companion and me to take refuge in a cistern, where for nearly an hour we were confined, listening to the rattling peals of thunder and torrents or rain. The effect of half the lake in perfect rest, while the other half was in wild confusion was extremely impressive. It would have fared ill with any light craft caught in mid-lake by the storm, and we could not help thinking of that memorable occasion on which the storm is so graphically described as ‘coming down’ upon the lake.