The men of the bedaween wear a white cotton shirt, the kamise of the Arabs, a black goat’s hair sackcloth cloak, and are specially distinguished by their headdress, consisting mainly of a large flowing scarf of silk or cotton, called kefeeyah, bound round their head by and akal, a twisted rope of goat’s or camel’s hair, generally about two inches thick. Artists say this is the most picturesque headdress worn by men. ON their feet they wear sandals, or, when riding, red leathern turn-up and pointed-toed top boots, very stout and clumsy, called jezmeh. The sandal is a stout sole of leather under the foot, which is bound to it by a thong, or string of hide, passed round between the ankle and the heel, and the brought over the top of the foot and between the treat toe and the second toe, and fastened to the sole by a leathern button. This is no doubt “the sandal” of the Bible, spoken of sometimes in our Authorized Version as “the shoe,” for it was worn by the poorest of the fellahheen as well as by the bedaween. When sending out his fellahheen disciples as poor men, our Lord told them to “be shod with sandals, and not put on two shirts.” The angel who appeared to Peter in prison said, “Bind on thy sandals.” The dress of the women of the bedaween is a long robe of indigo blue cotton, with an indigo blue or dark green cotton headdress and veil.

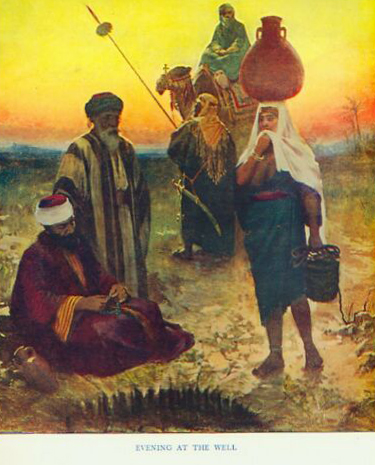

The fellahheen are the farmers and farm laborers. The name is derived from the Arabic, fellahh, “cultivator,” or “ploughman,” and they live in the unwalled villages and till the soil. The distinction between towns and villages, just as we find it today, is carefully made in the law of Moses. The city had a wall round it, and was entered by gates; while the village was without a wall and gates. (Lev 25:29-31) It is true that we read of the gates of some villages, as the gate of Bethlehem (Ruth 1:22) and of Nain (Luke 7:12); and that, speaking of villages as well as of towns, it said, “judges and officers shalt thou appoint in all thy gates.” (Deut 16:18) But in these cases the word “gate” is used by way of metaphor for “principal place of entrance” in the closely clustered group of village houses, where, as at the literal gates, of towns, the market and court were held. These villagers, the “cultivators,” are, and always were, the bulk of the population in all Oriental lands, the ‘am ha-arets, “the people of the land” of the Hebrew Bible, the polus ochlos, the “great crowd,” this is, “the masses,” of the New Testament, of whom we read when the Master spoke “they heard Him gladly.” The fellahheen, as shown by their representative in this picture, wear as their only garments a white cotton shirt, or tunic 0 the kamise of the Arabs, and the chiton of the New Testament, translated “coat” – very wide and full, which reaches to the ankles; but which, when they gird, that is, fasten their leathern or coarse worsted girdle round their loins, they take up at the front and tuck into the girdle, leaving their legs naked from the knee downwards, so as to be free for work. “Girding,” therefore, stands as a figure of preparation for, or engaging in, work, service, travelling, or warfare. Girding and the girdle also stand for “strength.” On the other hand, to “loosen the girdle” is “to weaken.” The girdle, too, is also used as a metaphor to represent that which clings closely, for it is the only tight-fitting part of Oriental dress.

Over the chiton they wear a striped brown and white or indigo blue and white goat’s or camel’s hair cloak, the stripes of which are always perpendicular. It is not only made of sackcloth, but it is roughly in the form of a very broad long sack; open down the front, and with two small apertures on either side at the top, through which the hands are put. This is called in Arabic aba, or abaiyeh, or meshleh. It is sometimes made of coarse worsted. It is, when made of hair, quite waterproof. For a great part of the year it is seldom worn, the fellahh working in his kamise, or shirt, alone. It is the “cloak,” “garment,” “raiment,” or “vesture” of our English Bible, wherever the fellahheen are alluded to, the salmah, livoosh, malboosh or adereth of the Hebrew Old Testament, and the himation, himatismos, or enduma of the Greek New Testament.

The head of the felahh, as of all other men in the East, is close shaven, and his headdress is the turban, consisting of four parts, a small skull cap of soft, white felt, over this another skull cap of white cotton cloth called arukeeyeh or takeeyeh, surmounted in turn by a red cloth fez, or tarboosh, with a huge black or indigo blue silk tassel, and wound round all in a liffey, a scarf or shawl, of wool, cotton, or silk. This is the fellahh’s pocket-book, where, in its several recesses, he carries his letters and papers, just as his “purse” is in the Greek zonee, “girdle,” in Matt 10:9 and Mark 6:8.

He has rude, natural-colored or red leather shoes, coming to a point, and turned up at the toes, the Arabic surmaiyeh, and these shoes he often carries in his hand when in full dress, for the soles of his feet are as well tanned as the Hebron leather – why should he wear shoes? The foregoing are all the clothes worn by the fellahheen.

Their women, the fellahhat, wear no underclothing or stockings, but only a long indigo blue cotton kamise, or tunic, down to their ankles, very full, like that of the men, with wide, long sleeves, and a girdle of dark red woolen or cotton cloth. Their headdress consists of a white cotton skull cap, over this a heavy red cloth tarboosh adorned at the front with rows of coins, and an immense veil attached to the tarboosh in the form of a sheet of cotton cloth about four feet six inches square. They have, for a cloak, an aba or abaiyeh, something like that worn by the men, but not so wide or long, which they only put on at times; and leather shoes, either natural-colored or red, similar to those of the men, though, for the greater part of the year, like the men, they go barefooted. These are ordinarily all the clothes they wear. The fellahhah in our picture, who has come to fill her pitcher at the well, is girded for walking and work; for the women gird in the same way as the men. “The mother of Jesus” must have dressed and lived as one of these fellahhat.

The third condition of Eastern life is represented by the belladee, or townsman, who is seen in our picture seated on the ground. The belladeen are the dwellers in the bellad, or ”town,” the polis of the Greek New Testament, which, as we have seen, is distinguished from the kom, or “village,” by being surrounded by a high wall with large and strong gates, which are closed at nightfall.

They are the merchants, shopkeepers, artisans, ministers or teachers of religion, scribes (the writers or learned class), the high governing officials, and the soldiers whose barracks, as in New Testament times, adjoin the governor’s palace, known as the Serai, or “Residency.” The dress of these belladeen is much more elaborate. Their numerous garments, though differing wholly at all points from ours, inasmuch as they are exceedingly loose, flowing, comfortable, healthy, and most artistic, are numerous, and they wear socks, jerebat or kelsat, an inner slipper of soft leather, kazzsheen, and over this the surmaiyeh, or shoe.

They are specially distinguished by two robes, the kumbaz or kuftan, an over tunic, and the cloak, the jibbeh, or jook, one form of which is called beneesh. The kumbaz is a long dressing-gown-like garment, which is open down the front, but worn lapped over and closed. It is then bound together round the waist by the zunnar, or girdle, in this case a scarf or narrow shawl, often five yards long, of silk, cotton, or woolen cloth, brightly colored. This robe, which is made of cotton or silk, has always a pattern of vertical straight stripes, sometimes of all the hues of the rainbows, though read and gold alone are very favorite colors. The sleeves of the kumbaz or kuftan are very long, extending some three or four inches beyond the fingers’ ends; but, dividing at a point about the middle of the forearm, they hang down so as to leave the hand exposed.

The cloak, which answers to the aba or abaiyeh of the fellahheen, the jibbeh, though loose and sack-like, and open entirely down the front, has wide sleeves, and is of fine cloth, often lined with fur, and dyed in all manner of bright, pure, self colors – red, blue, orange, purple, green, etc. The sleeves of the jibbeh, which end at the wrist, are much shorter than those of the kuftan, which hang down some ten to twelve inches below them. The beneesh is a cloth robe like the jibbeh, with long sleeves divided like those of the kuftan but ampler. There is also another cloak similar to the beneesh, called farageeyeh, with long, wide sleeves which are slit. Their headdress is the turban, similar in most respects to that worn by the fellahheen, but the liffey, or shawl of the turban, is larger, cleaner, and of lighter and more delicate colors and materials. L This is the full dress.

But the young men, servants, and tradesmen often wear very large, loose pantaloons, gathered in at the ankles, and drawn together and held in position at the waist by a cord, or sash, called dikky. In this case a sudereeyeh, or waistcoat without sleeves, is worn, which is buttoned up to the neck with numerous ornamental buttons, and, over the waistcoat, an elegant zouave jacket, the kubran. The women of the belladeen class will be described in connection with other pictures.

There never were many towns in Bible lands, and the comparatively few references to belladeen life in Scripture are mostly in the case of the courts of kings, and when the prophets are denouncing luxury, or when we read of the priests and Levites who were assigned forty-eight towns in Palestine, including the six cities of refuge, in which they were commanded to reside, for they were specially forbidden to cultivate land or live like the fellahheen. (Num 35:1-15) Of agricultural holdings they possessed none; for Joshua, at the division among the tribes, gave the Levites “no inheritance among them…no portion…in the land, save cities to dwell in, and their suburbs for their cattle and for their substance.” (Josh 14:3, 4)

The Lord Jesus was unquestionably a fellahh, as were most of the apostles. Nothing is clearer than this. Christ was born in the village of Bethlehem. He was taken, at about one to four years of age, to the village of Nazareth, where He lived in the home of Joseph, the village carpenter, for at least twenty-eight years. Cast out of Nazareth, at the commencement of His ministry, He chose a new home in the village of Capernaum, represented now by the ruins of Tell Hum, which, though extensive, have not surrounding wall with gates, and so mark a village. When the Lord came up to Jerusalem He never seems to have spent a night in the city, but lodged with His humble friends, Mary and Martha, and their brother, Lazarus, peasants like Himself with whom He would feel at home!

As a fellahh our Lord would have worn only five articles of clothing, namely: —

1. A kamise, or long cotton shirt.

2. A leather or coarse worsted girdle worn round the kamise.

3. A turban.

4. Shoes.

5 An aba or abaiyeh, a cloak made of goat’s or camel’s hair sackcloth or of coarse worsted.

It is often asked upon which of these did the soldiers cast lots. The first four were about equal in value, and each of the four soldiers would naturally agree to take one of these such as he needed. But the fifth, the aba or abaiyeh, is some three times the value of each of the other four articles of dress, and would naturally be the one over which is sometimes, especially in the region of Northern Galilee, “Woven without seam from the top throughout,” and is then of still greater value. (John 19:23)

The well in the midst of the group is simply a boring in the ground, surrounded at the mouth with a ring of stone, worn through long years into deep grooves by the rope being drawn up against it, as the bucket full of water is raised. There is “nothing to draw with,” no windlass, bucket, or rope attached to an ordinary Eastern well. Travelers carry their own bucket and rope about with them. The bucket used for this purpose, it will be seen, is a small one, much longer than it is broad, made of leather, so that it can be easily carried about without getting broken. Christ and His disciples were so poor that they had not this means of obtaining water, and hence the Savior’s opportunity of engaging the woman of Samaria in discourse by addressing to her the words, “Give Me to drink.” It is a serious breach of Eastern etiquette to speak to a st4range woman, rendered graver in this case by the one speaking being a Jew, and as such hateful to all Samaritans. In fact, when the disciples came back we read “they marveled that He talked with a woman” – not “the woman,” as in the Authorized Version. But even an Eastern woman may be appealed to by a parched and thirsty traveler, who could not otherwise obtain water, asking her for a drink. It was in this way that Abraham’s servant was able without offence to enter into conversation with Rebekah at the well in Mesopotamia. (John 4:7, 17; Gen 24:14, 17)

He, Who was so poor the He had not where to lay His head, and must needs take long journeys without the ordinary and most necessary accessories f travel – Who, as the apostle says, thus “became poor that ye through His poverty might become rich” – now, by means of this very poverty, was enabled to bring the riches of His grace to the heart of this poor sinful woman, and though her to so many of the men of her village.

The fetching of water, which has constantly to be brought a distance of a quarter of a mile of a mile form the spring or well, falls to the women. It is heavy work, for the earthenware vessel used for this service is a very large one. A powerful friend of mine, when a young man, the late Mr. H. A. Harper, the eminent painter of Palestine scenery, when on once of his first visits to the Holy Land, told me he saw a fellahhah, or peasant woman, trying to lift her waterpot when it was full, and, contrary to the stringent etiquette of the East, of which he was not then aware, like a gallant young Englishman, attempted to help her. He said to me, “I confess with shame I could not lift the pot a foot from the ground. Just then another woman came by, and the two between them raised it without any difficulty, and placed it on the pad upon the carrier’s head, and she bore it off with ease to her home.” It is this practice of carrying a such a heavy weight on the head that gives these fellahhat and the women of the bedaween the fine figures and graceful carriage shown in these pictures, and which artists have so greatly admired.

The work of drawing and carrying water is only done by women. Men call it shougal niswan, “women’s affairs,” and, with the powerful caste spirit of the Orient, would scorn to take part in it. Hence appears the striking and hitherto unsuspected character of the sign which the Lord gave to His two disciples, Peter and John, by which they should know where to prepare the Passover, “There will meet you a man bearing a pitcher of water; follow him into the house where he enters.” To the ordinary English reader this seems likely to be too common an occurrence to form any certain and striking sign. But so far from this being the case, it was in Jerusalem then, as it would be today, a truly strange and altogether exceptional thing. In all probability this was the only man in the city that day bearing a waterpot, and it is difficult to understand how he had come to do such work. Peter and John must have marveled when the sign was given them, and still more when they witnessed its miraculous fulfillment, and thus knew for certain the house to which the Lord would have them go. (Luke 22:10, 13; Mark 14:13-16)